Source: El País

By: Eva Güimil

On April 15, 1975, twenty-one-year-old Karen Ann Quinlan collapsed into the arms of a friend in a Morristown, New Jersey, bar. They took her home and tried to revive her; then they called 911 and although the ambulance only took 15 minutes to arrive, she never woke up again. Five hours after she was admitted at the Newton Memorial Hospital, doctors diagnosed her with brain death and put her on a ventilator. The cause had been an ingestion of alcohol and tranquilizers, specifically a combination of Valium and gin and tonics that struck down a body that had not eaten for several days: according to her relatives, Karen was very worried about getting into the new dress that she had bought to attend a party that night.

Karen’s memory has been fading, but she even sneaked into pop culture in some cases very surprisingly, such as when, on December 1, 1983, Glutamate Ye-Ye sang The Ballad of Karen Quinlan in The Golden Age amongst Atlético de Madrid soccer club flags.

Her parents, who did not know that facet of Karen, listened in shock to the story of the last days of a daughter’s life that they did not recognize in that story of alcohol and pills. And although they did not know then that the worst part of their hell had just begun and, with it, one of the greatest controversies of the 70’s and a debate that has not yet ended.

Karen was born in Pennsylvania on March 29, 1954 and just a couple of weeks later she was adopted by Julia and Joe Quinlan, their parish secretary and a parts factory accountant and World War II veteran, two devout Catholics who had opted for adoption after several miscarriages. Karen was a good student who used to ski, play tennis, swim and sing in the school choir.

At the age of four, in front of an ice cream, her parents revealed her that she was adopted. By then she already had two brothers whom she taught to ride bicycles and climb trees. The biggest frustration she had caused her parents was when she refused to attend university: they wanted her to study architecture but she preferred to work in a small pottery shop. Five months later, she returned home devastated: she had been fired. She was so crestfallen that her father went to speak to the manager to find out what had happened. It had not been for something she had done, just an economic adjustment of the company. Yet for Karen it was the first step of a personal debacle from which she never recovered.

She moved into a house with some friends, started working at a gas station, and bought a small Volkswagen. For her parents she was still their little girl, the good sportswoman with the prodigious voice, but her longtime friends noticed the change: she was drinking more and eating less. Her former boyfriend, Tom Flynn, stated, as The New York Times reported, that she had called him two weeks earlier and asked him to resume their relationship. He refused but agreed to see her that April 14: Ka-ren never made it to the appointment.

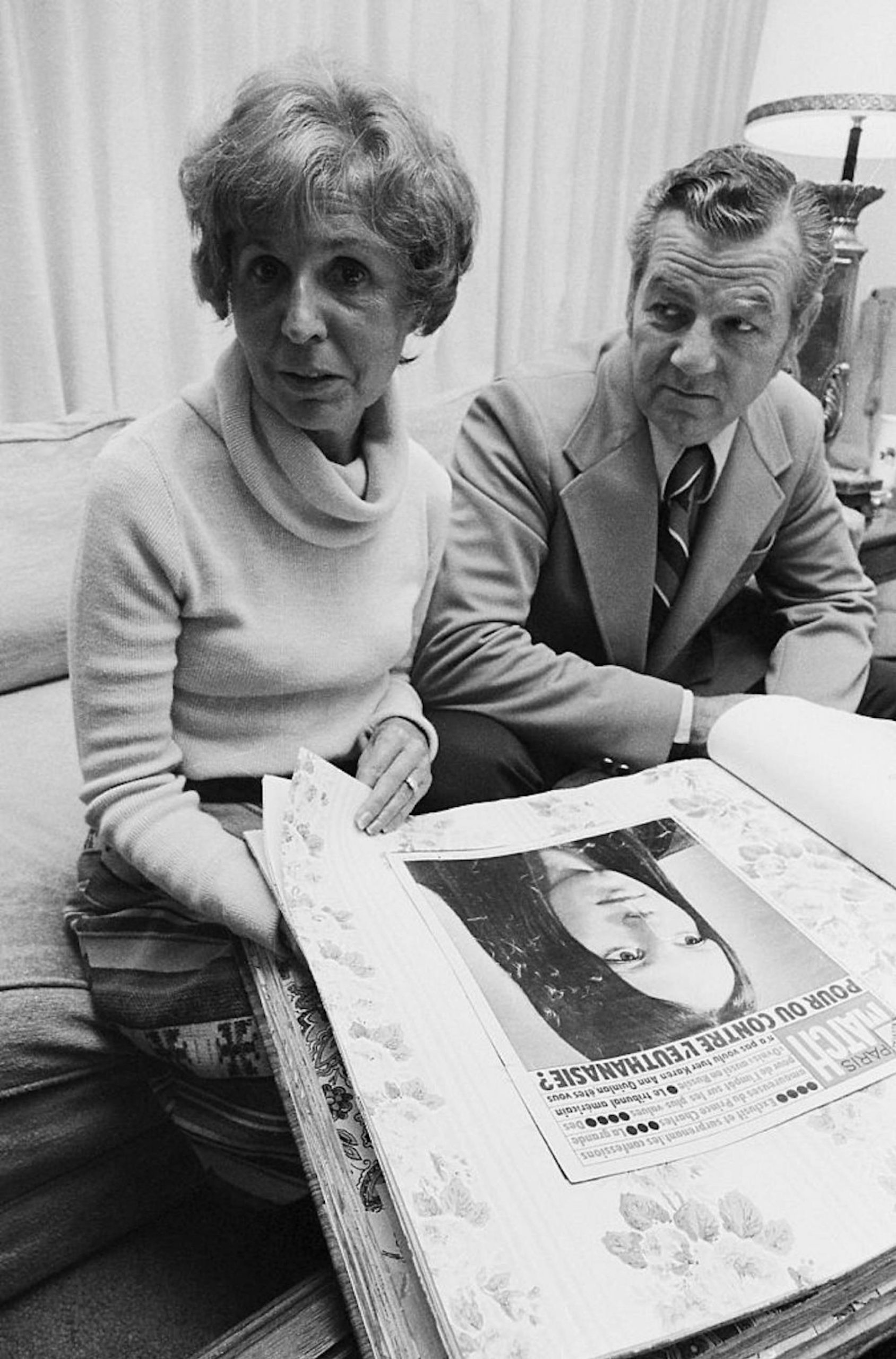

On the advice of their lawyer, the Quinlans changed their phone number, deleted their name from the mailbox and got used to living surrounded by photographers who chased them even when they took out the trash.

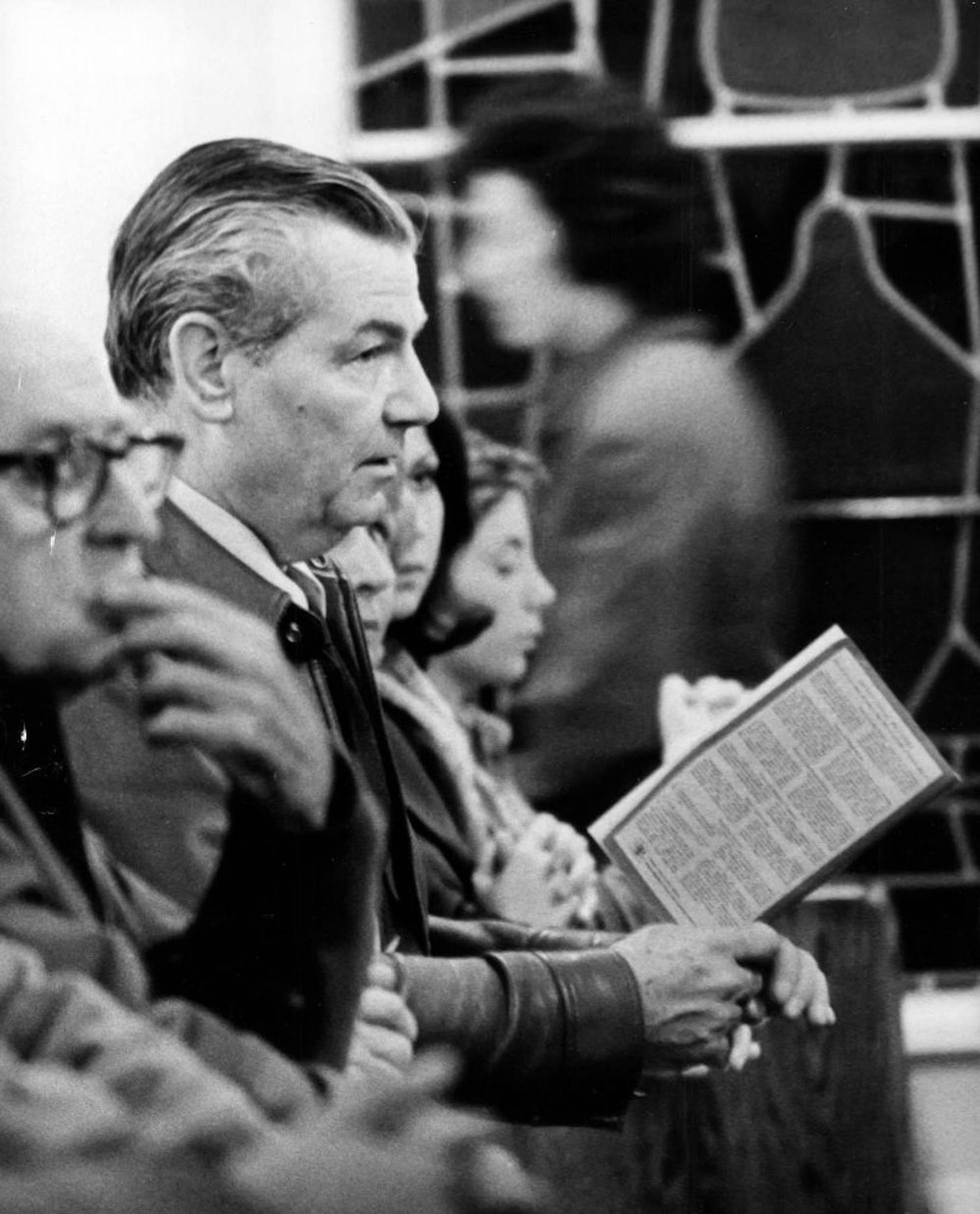

After three months during which the Quinlans watched helplessly as their intubated daughter went from fifty-two kilos to barely thirty, they decided, despite or precisely because of their strong Catholic convictions, to ask that Karen be disconnected from artificial respiration. They wanted their daughter to die naturally “with grace and dignity”. So was revealed by Julia Quinlan in her book The True Story of Karen Ann Quinlan, written to defray inordinate expenses that just over the first five months had amounted to more than two hundred thousand dollars. They had been advised by priests and experts: Karen was not going to come back to life. The hospital doctors refused to disconnect her for fear of being charged with murder, and the law required to use all resources available to keep alive a patient.

An unprecedented fierce legal battle then began with echoes around the world, a world divided between those who believed that Karen had to be kept alive and those who considered that that was not life. Karen’s case had become a symbol for those who defended the right to die with dignity. An inordinate responsibility for which that married couple and their adolescent children were not prepared. On the advice of their lawyer, they changed their phone number, deleted their name from the mailbox, and got used to living surrounded by photographers who chased them even when they took out the trash.

That is why Karen remained in a secret room at Saint Clare’s Hospital, the location of which was only known, in addition to her parents, to the director of the hospital, her two doctors, two nurses, the family lawyer –Paul Armstrong– and the priest Thomas Traspasso. The elevators did not stop on that floor and the stairs exit was also locked. Four police officers guarded the main entrance of a hospital that was impossible to access with a camera and each person who entered had to fill out a questionnaire, which did not prevent a photographer from trying to sneak into the room disguised as a nun and countless of healers tried to approach her to become famous. She was the U.S. most famous patient and the media monitored the hospital 24 hours a day.

The New Jersey Superior Court refused to disconnect her on the grounds that there was a remote possibility that she would wake up: shortly before, a young man who had been in a coma for eight years after a car accident had come back to life. However, his injury was reversible, not as Karen’s. The Quinlans never gave up and finally the Supreme Court of New Jersey agreed with them in a historic decision “because no best interests of the State can force the patient to endure the unbearable”. The court also ruled that no one could be criminally responsible for removing the life support systems, because the death of the woman “would not be homicide, but expiration from existing natural causes”. “This is the decision we have been praying for during a long, long time. It is the right decision,” the Quinlans declared.

“Who will kill Karen?” wondered in 1976 Alberto Oliva, in a long report of the first issues of the newly founded Interviú magazine, with regard to the name of the nurse or doctor who would finally separate her from life. The Spanish media were not indifferent to the fascination that this case aroused and the stare into space of “the sleeping beauty”, as some called her, multiplied in Pronto, el Nuevo Vale or El Caso that every week published the most shocking and scandalous data in history, real or not, while the newspapers opened their pages to the debate on dignified death.

Ten thousand kilometers away from the hospital where her body rested, her evolution was followed like the plot of another series because Karen could be any of the Spanish teenagers who were beginning to cling to her imported Winston and her Larios with tonic in a Spain that was beginning to shake off forty years of gray. With her straight hair and conventional appearance, she could be a typical photo of a New Jersey or a Salamanca University graduated. Karen Quinlan was like a blank canvas on which any young woman could project her story.

However, when the artificial respirator was disconnected Karen’s small body continued to struggle. No one knew how long she could hang on to life, but her parents never requested to stop feeding her artificially until God decided, which opened another debate about how far life went.

That year, she was transferred to the Morris View nursing home where she could be given proper care and her family visited her twice a day. Despite being fed through a nasogastric tube, her body continued to weaken. The idealized image shown by some media of a young woman with straight hair resting peacefully on her bed was unreal: during all her vegetative-state life she remained in a fetal position, stiff, and suffering strong spasms.

But for those who observed the phenomenon from a distance, Karen was still the young woman in the portrait, a portrait that slipped into Spanish homes thanks to Historia de Karen, by Ernesto Frers, published by Ediciones Martínez Roca and a whole best-seller from Círculo de Lectores. The story of the girl in a coma was mixed in the same collection with the adventures of the wayward Christina Parker, immortalized by Linda Blair in Born Innocent. Both stories were as moralizing as they were alarming, but Karen’s was real.

Ten years after the law allowed her to be separated from her respirator, she died in her room at the Morris View nursing home. On June 11, 1985, at seven in the afternoon and due to a respiratory failure, as reported by EL PAÍS. Her mother held her hand for the last time. “I don’t think you can prepare yourself one hundred percent for the death of a child. Karen lived in a state of limbo and my family and I lived in a state of limbo. I cried for Karen for ten years and now I had to cry again,” Julia Quinlan told the Los Angeles Times. Karen was buried in the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in East Hanover.

Karen’s life and death forever altered the peaceful existence of the Quinlan. In 1980 they founded the Karen Ann Quinlan Hospice to provide home care for terminally ill people. According to the institution’s website, it was the fight for their daughter’s rights that opened their eyes to that need and they promised that lack of money would never be an obstacle to entering the center. Julia Quinlan continues to run the hospice with her children Mary Ellen and John. Her husband Joe passed away in 1996.

Karen’s memory has been fading, but she even sneaked into pop culture in some cases very surprisingly, such as when, on December 1, 1983, Glutamate Ye-Ye sang The Ballad of Karen Quinlan in The Golden Age amongst Atlético de Madrid soccer club flags. That young woman in a fetal position who had never left New Jersey had become a popular figure. Her death in 1985 coincided with a trip to New Jersey by Morrisey who two years later would sing Girlfriend in a coma, almost without being aware of the origin of a hymn that has been over-performed ad nauseam. Two decades later another pop icon, Douglas Coupland, author of Generation X, would make her the protagonist of a very similar story, but with a more optimistic ending in The Second Chance. The real Karen only had one.

Source: El País

https://elpais.com/elpais/2020/06/10/icon/1591781563_862825.html

José de Teresa 253, Campestre Tlacopac, Álvaro Obregón, CP 01040, CDMX

AVISO DE PRIVACIDAD Copyright© DMD México | Cuarto Negro 2024