Source: Newsroom

By: Jonathan Milne

A scientist convicted of helping his terminally ill mother die has written to the Prime Minister seeking a pardon – expected to be the first of several such pleas for mercy. He speaks with Jonathan Milne.

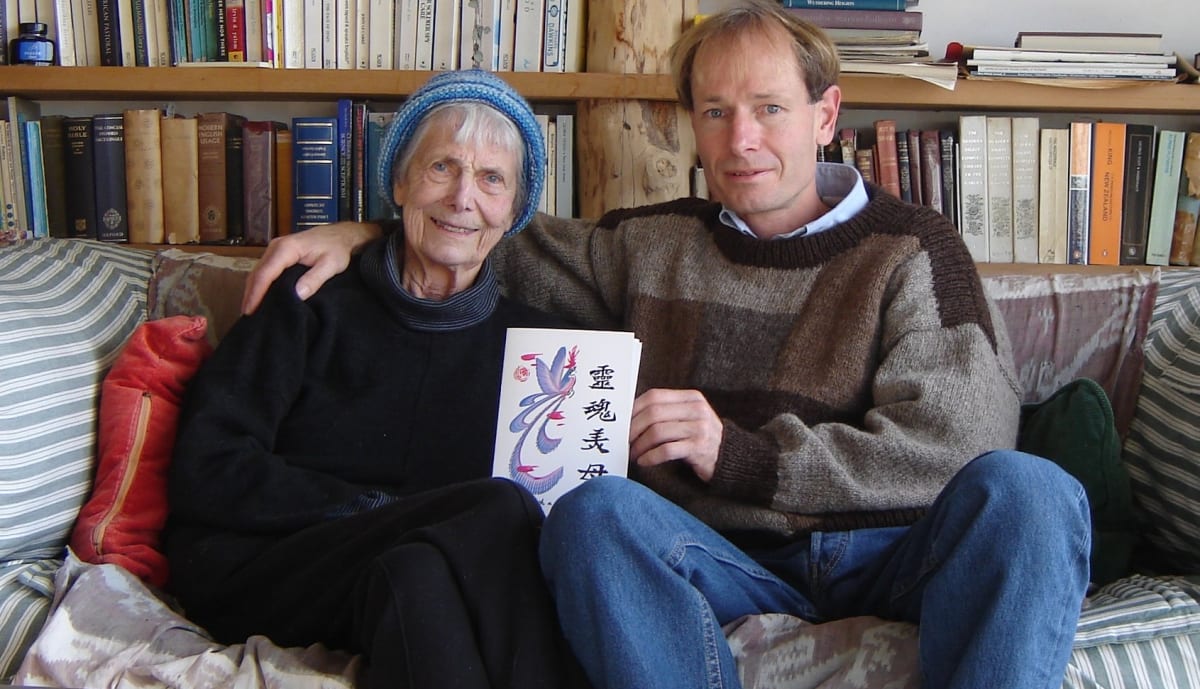

Sean Davison was called home from South Africa to care for his dying mother. Dr Patricia Ferguson was terminally ill with cancer; she was trying to starve herself to death but suffering the very protracted misery she had sought to avoid. She pleaded with her scientist son to help her to die.

“I was very focused on making each day as pleasurable as possible – in a way I was focused on keeping her alive,” Davison says now. “It seemed incomprehensible to end her life.

“After much soul searching I realised that it was not my choice, it was my mother’s. Who was I to play God and tell her that she must continue rotting in her own bed until her death? It was her decision.”

He finally acceded; he gave her a lethal dose of crushed morphine tablets mixed with water.

That such a tragic story can be told in such abrupt and prosaic terms speak to its familiarity. Not just the familiarity of Davison’s experience, but of other sons and daughters, husbands and wives, sisters and brothers and friends.

Nurse Lesley Martin was sentenced to 15 months for the attempted murder of her dying mother, Joy. Evans Mott was discharged without conviction after admitting a charge of aiding and abetting his wife Rosie’s suicide. Suzy Austen, a euthanasia campaigner with Exit International, was convicted for importing pentobarbitone used by some people to end their lives. And for every case to make the headlines, there are others who die quietly at home with few questions asked.

Davison was charged with attempted murder; he agreed to plead guilty to assisted suicide. He was sentenced to five months’ home detention, finally returning to his wife and children in South Africa in May 2012.

There, he became a prominent voice for assisted dying. Last year, in the Western Cape High Court, he was sentenced to three years house arrest for his involvement in the deaths of three men: his friend, Dr Anrich Burger, who became a quadriplegic after a car crash; Justin Varian, who had motor neuron disease; and 32-year-old athlete Richard Holland, left with locked-in syndrome after a cycling crash.

“I would be grateful if you would consider a formal application for a pardon for the assisted suicide conviction I received in 2011. If the new law had been in place then my mother would not have gone on a hunger strike, content in the knowledge that she could have had a legal assisted death if her suffering became too great. I would not have been asked to help her to die, and I would not have a criminal record for doing so.”

Dr. Sean Davison

Now, with the End of Life Choice Act referendum legalising assisted dying in New Zealand, 59-year-old Davison has written this week to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. “I would be grateful if you would consider a formal application for a pardon for the assisted suicide conviction I received in 2011,” he wrote.

“If the new law had been in place then my mother would not have gone on a hunger strike, content in the knowledge that she could have had a legal assisted death if her suffering became too great. I would not have been asked to help her to die, and I would not have a criminal record for doing so.”

His application for a pardon will not be the only one.

Law Professor Andrew Geddis, at the University of Otago, points to the precedent of Parliament quashing historical convictions for homosexual acts. This was done by passing a law that set up specific criteria for who qualified to have their convictions expunged, what sorts of convictions were covered, and how that process was to take place.

“It didn’t have to be done this way,” Geddis points out. “The Government could in theory have used individual decisions to grant, or not grant, the prerogative of mercy to expunge convictions.”

The advantages of a law change, to expunge convictions connected to helping loved ones die, was that it clarified who qualified, and what the legal effect was of the convictions being quashed. Legislation also represented all of Parliament, not an individual Minister.

“Even if we’ve now decided that the terminally ill who are suffering should have a way to end their lives, is that the same as saying that we think the criminal law ought not to have applied to those who carried out such actions in the past?”

Professor Andrew Geddis

“What about those convicted of aiding people to die in the past? There’s going to be far fewer of these convictions than was the case for convictions for homosexual men,” he says.

“As a society, we’ve accepted that it never was right to make gay men criminals. Even if we’ve now decided that the terminally ill who are suffering should have a way to end their lives, is that the same as saying that we think the criminal law ought not to have applied to those who carried out such actions in the past?”

For Minister of Justice Kris Faafoi, the answer is “no”.

“There are no plans to legislate for the quashing of historical convictions for assisting suicide or related offences.”

He says the End of Life Choice Act did not decriminalise aiding a suicide. It established a detailed procedure and eligibility criteria for somebody to request and receive assisted dying, which would involve oversight, transparency and accountability. “Historical cases, which resulted in convictions, would not necessarily have been eligible and therefore legal under the End of Life Choice Act.”

“The social context regarding assisted suicide is not comparable, nor is the nature and consequence of the actions involved where a person takes another person’s life.”

Kris Faafoi, Minister of Justice

Faafoi says the Criminal Records (Convictions for Historical Homosexual Offences) Act 2018 was the only precedent in New Zealand for wiping convictions on the basis that the conduct was no longer regarded as criminal.

“That legislation was enacted because societal views towards homosexuality have moved so far that the law criminalising homosexual acts is now viewed as highly discriminatory and manifestly unjust,” he argues.

“The social context regarding assisted suicide is not comparable, nor is the nature and consequence of the actions involved where a person takes another person’s life.”

But Davison, a professor at the University of Western Cape, believes that is missing the point. There was no legal framework of any kind to give people like his 85-year-old mother a choice about how she died. She was not allowed to take her own life; she was not allowed to ask him for help; she was not allowed to ask her doctor.

“It is wonderful that New Zealand has approved this new end-of-life law, and hopefully this will provide a stepping stone for a law that goes beyond the suffering of the terminally ill,” Davison says.

“If the new law was in place at the time when my mother was dying, she would certainly not have gone on a hunger strike that made her final weeks so dreadful. She would not have been in the situation where she had to beg for help to die, and I would not have been charged with murder for helping her to die.”

Suzy Austen, convicted of importing a Class C drug

Suzy Austen is another who feels her hand was forced by the lack of an assisted suicide law. The euthanasia campaigner smuggled the drug pentobarbitone in her toilet bag (“I haven’t admitted that to anyone!”) coming back into New Zealand.

Those days of international travel are now all but over.

She was convicted of two counts of importing a Class C drug, convicted, and fined $7500. She was found not guilty of assisting Annemarie Treadwell’s 2016 suicide.

Austen, an outspoken euthanasia campaigner at 69 years old, wears her conviction as something of a badge of honour. But it does mean she and her husband can no longer travel to the US, as they loved to do, nor to Britain for the foreseeable future.

She believes strongly that people like Davison and Lesley Martin should not have criminal convictions next to their name; that the Government should quash their convictions. “They were doing it out of absolute love and compassion for their mothers.”

And for herself and her 90-year-old husband, in order to see friends and family overseas while they are still healthy enough to travel, she would like her conviction quashed.

“I’m not ashamed of having a conviction, for what it is. I believe in choice,” she says. “But I applied to go to England to visit family but wasn’t allowed, because of my conviction. And Mike loves America.”

And she worries that she won’t be allowed to accompany her grandchildren on school trips, because she will fail the police vetting. It’s these little thing about a conviction that can be degrading.

Evans Mott, discharged without conviction

The actions of Auckland man Evans Mott, in helping his wife die in 2011, were courageous, a court was told. He was her “hero” in helping end her suffering from an aggressive form of multiple sclerosis, his lawyer said.

Back then, Evans and Rosie Mott lived in a house on Auckland’s distinguished Paritai Drive. Now, nine years later, the 69-year-old Mott lives in a converted shipping container at Red beach, on the Hibiscus Coast. After all this time, he still can’t quite believe he walked free from that courtroom.

He had helped his wife research suicide methods and assembled a kit for her.

Before her death, Rosie Mott pleaded with her husband to deny all knowledge. She insisted he live the house in her final hours, so he could not be found culpable. He returned several hours later to find her dead, lying peaceful.

“She shouldn’t have had to die alone,” he says. “I should have been there at her side, holding her hand.”

Mott wants everyone convicted in connecting with assisted dying to be granted an individual, case by case review, to determine whether they should be pardoned. He doesn’t know the details of Martin, Davison and Austen’s convictions, but says he’s seen nothing to indicate they acted with other than complete compassion and humanity.

Davison, Austen and Evans Mott all believe the End of Life Choice Act should go further than it does; that anyone suffering a debilitating should have the right to choose how to end their suffering; not just those facing imminent death.

‘My crime was out of compassion’

Sean Davison says the referendum vote supporting the End of Life Choice Act vindicates his actions in helping his mother to die. “However, I never felt I needed this vindication, or justification,” he adds.

“Although I broke the law at the time, I hope the government will now consider my ‘crime’ as an act of compassion. I acted out of compassion to end my mother’s suffering and do not want to be branded as a criminal for doing so.

“For me a pardon will finally bring closure to my mother’s death.”

José de Teresa 253, Campestre Tlacopac, Álvaro Obregón, CP 01040, CDMX

AVISO DE PRIVACIDAD Copyright© DMD México | Cuarto Negro 2024